This is a follow-up story to the special report “Bright spots in the dark: Tracking Malaysia’s fiscal transfers for nature conservation”, a co-publication by Eco-Business and Macaranga.

In 2019, the Malaysian federal government disbursed RM60 million (US$13.4 million) to state governments to incentivise them to conserve protected areas. This mechanism, known as an Ecological Fiscal Transfer, has seen Putrajaya allocating a total of RM800 million (US$178.9 million) since.

Despite a lack of clarity on how Malaysia’s state governments have used EFT funds, conservationists broadly agree that the mechanism is a positive one for biodiversity protection.

Lakshmi Lavanya Rama Iyer, WWF-Malaysia’s policy and climate change director, said she is encouraged to see that the EFT scheme has evolved over the years and that “very important, central government ministries” like the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Economy “are understanding and embracing the idea”.

But the EFT mechanism is far from perfect, and conservationists say there are many ways in which it can evolve to better value and protect Malaysia’s forests and marine ecosystems in the long run.

The EFT is evolving

Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, minister for Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability (NRES) agrees that the EFT needs improvement, and said that his officers are working on it.

“This year, we’ve made 50 per cent (of the allocation criteria to states) based on the size or quantity (of land and marine protected areas), and (the other) 50 per cent is evaluated based on the quality of conservation work,” he told Eco-Business. Before, it was 70 per cent and 30 per cent, respectively.

Image: Eco-Business

Allocating EFTs by land size has in some ways been an unfair criteria, say experts, as states with more land areas would always stand to receive more money, while unique, biodiverse ecosystems in smaller states are overlooked.

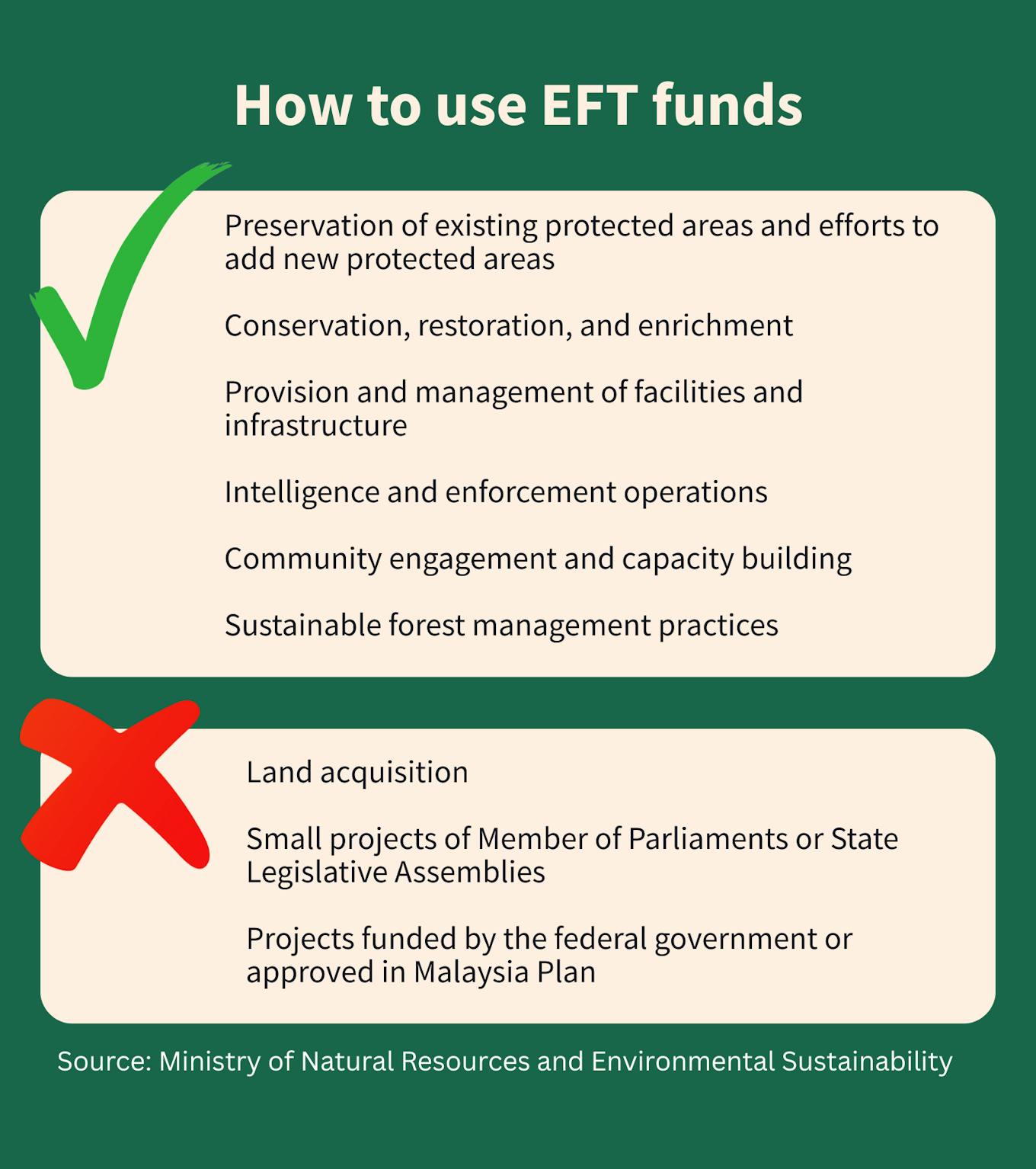

NRES also announced last month that it would add Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECM) to the scope of activities that can be funded using EFTs and distribute the funds twice a year, instead of on an annual basis. OECMs are areas that are not gazetted as protected areas, but which are managed to ensure long-term biodiversity protection and conservation.

WWF-Malaysia highlighted that there is no permanence to protected areas, as there is no requirement for states to keep forest reserves or other protected areas gazetted in the long run. Beyond just designating a site as a protected area, efforts must also be made to ensure that the area is well governed.

For example, a state could commit to gazetting 10 per cent of its total land area as forest reserves in order to secure funding for a specific number of years. “After those years, (the state) could decide that it wants to build a new housing estate that is going to give it lots of money, and so degazette the forest,” said Shantini Guna Rajan, national policy lead at WWF-Malaysia.

“We need to think about how we strengthen (mechanisms like EFTs), so that we don’t pour money into areas for nothing,” she added. “If conservation is at the heart (of the EFT) and it is targeted towards higher quality conservation outcomes, then we need to be very clear how we (scope the) eligibility criteria to target higher levels of protection or conservation.”

Conservationists in Malaysia say that allocating conservation funds based on land size alone could cause smaller, uniquely biodiverse ecosystems to be overlooked. Image: 57Andrew, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Flickr.

Make EFTs permanent

But beyond that, conservationists are hoping for legislation that would ensure the EFT mechanism is a permanent one. “What we want is certainty that there will always be an allocation (for EFT) in the federal budget,” said Lavanya.

Malaysia’s Budget 2022 mentioned that a minimum of RM70 million (US$15.7 million) in EFT would be allocated every year, but this is not legally binding.

NRES told Eco-Business: “Currently, EFT allocations are subject to the annual federal budget process and availability of government funds, which may vary from year to year.”

Environmental lawyer Preetha Sankar pointed out that EFTs have never had a concrete policy basis, despite having been mentioned in national documents such as the 12th Malaysia Plan.

“Fiscal measures like EFTs are essentially policy measures and deserve a strong, clear and foundational basis with strategies for adaptation over time,” she told Eco-Business.

EFTs in the five-year Malaysia Plans

EFTs are mentioned in the 12th Malaysia Plan as one of several mechanisms planned to diversify conservation funding. Specifically, the plan states that the EFT implementation mechanism will be set up in order to incentivise states to conserve conserving protected areas.

It is also mentioned in a chapter on water sector development as an innovative financing mechanism. “The EFT mechanism will be institutionalised by providing adequate funds and introducing an appropriate distribution mechanism. This mechanism will be based on the commitment of states to protect and conserve forests, especially water catchment areas,” said the plan.

Sankar believes the 12th Malaysia Plan was a missed opportunity to formalise EFTs. However, the upcoming 13th Malaysia Plan, which is currently being spearheaded by the Ministry of Economy and is meant to outline the country’s development strategy for the next five years until 2030 could include a more robust policy framework on EFTs, she said.

The need for speed

When the EFT mechanism was introduced in 2019, the focus was on speed. The federal government wanted to allocate funds for biodiversity conservation in the national budget before a full-fledged policy was developed, said Preetha.

Preetha was then a legal consultant with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). UNDP oversees the UN’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative, a global effort to raise funds for biodiversity conservation and protection, and has been a leading advocate for the EFT mechanism in Malaysia.

At the time, the federal government disbursed the funds under the Ministry of Finance’s ‘TAHAP’ scheme, which transfers funds to states for economic development, infrastructure and well-being.

Image: Eco-Business

But the creation of the EFT mechanism under the TAHAP scheme meant that the funds were not sustainable or guaranteed, said Preetha. That is because TAHAP grants are discretionary and periodic. “They were expedient, but not sustainable in the long-term or legally entrenched,” she said.

Since 2022, the distribution of EFT funds has been overseen by NRES, having been revised and placed under a “special allocation” to NRES from the Ministry of Finance.

But how much EFT allocation would be made every year – if any (there was none in 2020) – remains uncertain.

A recent statement by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, who is also the country’s minister of finance, reinforced the fact that the finance ministry ultimately holds the purse strings when it comes to allocating EFTs.

The need for legal guarantee

Currently, states are only guaranteed federal transfers based on two main criteria enshrined in Article 109 of Malaysia’s Federal Constitution: capitation, or population size, and the length of roads. All other transfers are discretionary.

“If we are to get very serious about EFTs, a constitutional amendment to add an ecological criteria grant in addition to the two (criteria) above can be initiated,” said Preetha. But as such an amendment may be politically complex, a more feasible option for the government would be to table a federal law, using Article 109 as a basis, she suggested.

A regulatory framework for EFTs could give the scheme more legitimacy, as the system could incorporate details of the necessary allocations, criteria, duties of the recipient state governments, as well as monitoring and reporting frameworks, she said.

NRES minister Nik Nazmi also believes there is a good basis to make the EFT a more permanent mechanism. But he said that more in-depth discussions will need to be had with the states. “The challenge for us is to match (what states are asking for) because they want a much bigger amount,” he said, given that the federal government also has many other commitments, such as financing of schools, hospitals and roads.

Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, Malaysia’s minister for Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability, told Eco-Business that states want a bigger amount allocated in ecological transfers from the federal government. Image: Malaysia Forest Fund/ LinkedIn

Getting states on board

The federal government could also tweak the EFT to better align state government interests with national conservation goals.

For example, Malaysia signed the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework in 2022. Accordingly, the federal government set new biodiversity targets, such as restoring 30 per cent of all degraded ecosystems and conserving 30 per cent of land, waters and seas.

But state governments have the final authority on matters of land and rivers. While the federal government could set policies and laws relating to land matters, state governments are not obliged to heed them.

An example is the amendments made by Putrajaya on the National Forestry Act in 2022. The amendments require that any degazettement of forest reserves be subjected to public inquiry, and replaced with a forest of equal or larger size at the same time.

So far, only the Perlis state legislative assembly and the federal territories have fully adopted the amendments.

“At the end of the day, it’s (within) the state’s power. The federal government can provide carrots or sticks, and we can advise the state government, but if they do not want to (adopt the act) it is ultimately a state matter,” Nik Nazmi said.

Shantini of WWF-Malaysia said that “the federal government cannot tell states what to do, but it can change the behaviour of states through enticements. But for that to happen, the size of the pot must be enticing enough, and how states can use that money and access it must also be enticing enough.”

Image: Eco-Business

Other conservationists are calling for the federal government to allow state governments to use EFT funds for non-conservation matters.

Lim Teckwyn, managing director of environmental consultancy RESCU, argued that giving more leeway over EFT funds usage would make the scheme more appealing to state governments.

Likewise, WWF-Malaysia’s Lavanya pointed out that EFTs must be considered among the other economic priorities of state governments, such as the construction of roads and schools.

“I think the bulk of (EFT funds) should go towards conservation, but maybe a certain portion, say 25 per cent, could be used by states for these other purposes,” she said.

Tighter alignment with conservation goals

One way of bridging the federal-state divide could be linking more fiscal transfers to conservation outcomes and state governments’ support for national biodiversity objectives.

“In addition to the EFT, there are billions of ringgit going to states every year from the federal government (for) development expenditure,” said RESCU’s Lim. “There is potential for some of that to be linked to conservation, even if not explicitly part of the EFT scheme.”

For instance, if states are openly going against or undermining national biodiversity objectives by clearing land in high biodiversity areas or areas containing endangered species, the federal government could renegotiate current funds.

“Of course, it needs to be done sensitively. The EFT does represent a little bit of this kind of federal-state bargaining, but it’s not being leveraged as part of the bigger programme,” he told Eco-Business.

There are also other federal-state financial arrangements that could be tapped to drive conservation financing, Lim added. Debt-for-nature swaps, for instance, could see the federal government writing off debt owed to them by state governments in exchange for a certain portion of its land to be pledged for conservation.

“

At the end of the day, it’s (within) the state’s power. The federal government can provide carrots or sticks, and we can advise the state government, but if they do not want to (adopt the act) it is ultimately a state matter.

Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, Minister of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability, Malaysia

Other financing options

Beyond EFTs, Malaysia needs all the biodiversity funding it can get – a 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) report said the country needs about RM2.4 billion (US$536.6 million) annually in biodiversity financing from 2018 until 2025. That figure is 10 times the RM250 million (US$55.9 million) EFT funds allocated in 2025.

“I empathise with state governments when they come to us saying, ‘You don’t want to cut down trees – what’s the replacement?’” Nik Nazmi shared. “Calculating (income from) timber is easy. (With) carbon markets, they see the talk but they don’t see the money. For states without commercial and industrial sectors, it’s a big issue for them.”

Aside from the EFT, there are several biodiversity financing avenues available or being developed in Malaysia. There is the federal government’s National Conservation Trust Fund, which has reportedly channelled RM21 million (US$4.7 million) to 112 conservation projects since it was established in 2015. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) mechanisms could be charged to protect key ecosystems such as water catchment areas or reserves. For example, Sarawak raised RM6.6 million (US$1.5 million) by imposing PES on developers or project proponents involved in building telecommunications towers and transmission lines within permanent forests.

Fish near the island of Sipadan in Sabah, Malaysia. Malaysia is one of the 17 megabiodiverse countries in the world. Image: Johnny Africa/ Unsplash

Furthermore, the federal Malaysia Forest Fund supports private investment via Forest Carbon Certificates and is developing a Forest Carbon Offset protocol, which will serve as a framework for forest-based carbon trading in Malaysia. The government expects carbon trading to escalate once the carbon tax on producers of energy, steel, and iron takes effect in Malaysia next year.

Beyond these, the government is open to other conservation financing solutions, said Nik Nazmi. “We want to find ways to be creative, since the government has certain limitations in terms of funding,” he said, although he added that some proposed solutions, such as biodiversity sukuks or rhino bonds, are not straightforward.

“The challenge is: how do we make (these) truly meaningful and effective?”

Whether it is EFT or another conservation financing mechanism, building a strong foundation for environmental governance is important, said WWF-Malaysia’s Shantini. This includes better defining protected areas and ensuring proper governance and management of those areas.

“If systematic problems are not addressed, then the tools being created cannot reach their full potential,” she said.

The report was developed and written with editing support from Ng Wai Mun and Macaranga’s YH Law.

This series was also produced with a grant from the Youth Environment Living Labs (YELL), administered by Justice for Wildlife Malaysia (JWM). The contents of this story do not necessarily reflect the views of YELL, JWM, and their collaborators.