• After years of living in a condo, the Hinch family was ecstatic about the giant backyard of their new Porter Ranch home.

• Then they got their first water bill of $3,000 and tore out much of their lawn.

• The Saddleridge fire in 2019 incinerated most of their remaining yard, so they created a less thirsty, more fire-resilient landscape heavy on native plants.

It was 12:30 a.m. on Oct. 10, 2019, and Phil Hinch was in his bed, “dead to the world,” when he heard someone pounding on the door of his Porter Ranch home. His wife, Margaret, was on a business trip in New York; their two young children were in their rooms, fast asleep.

The porch was empty when he groggily opened his front door, but he instantly understood why someone had been knocking.

“It was ‘Lord of the Rings’ out there, with a massive amount of sparks coming from the hill in front of us just pouring down our way,” he said. “I ran back and woke up the kids, grabbed some clothes, got the cats, threw everybody in the car and then we took off.”

Neighbor Dane Kalman shot this photo of the Saddleridge fire on Oct. 10, 2019, as the Santa Ana winds blew a tornado of embers from the hill across the street from Margaret and Phil Hinch’s Porter Ranch home. “It was ‘Lord of the Rings’ out there,” said Phil Hinch.

(Dane Kalman)

From the safety of his brother-in-law’s home in Van Nuys, Hinch grimly used his phone to watch an inferno of swirling sparks sweep through his yard.

The embers ignited everything in their path: trees, fences and the new plants and bark mulch Phil and Margaret had added just a few days before. He watched neighbors come into his backyard and vainly battle the flames. He saw fire ignite Margaret’s bee hives near the top of the hill (the bees escaped), and his daughter’s beloved playhouse become a silhouetted torch until it finally collapsed.

Around 4 a.m. the cameras went dead, and Hinch’s heart sank. “I thought, ‘That’s it for the house.’ ”

When Margaret woke up in New York, she turned on her phone and discovered she had 53 messages. A native of Twin Peaks, a mountain town near Lake Arrowhead, she was no stranger to fires. Once she learned her family was safe, she realized she didn’t care about the rest. “Things can be replaced,” she said. “Families cannot.”

But, as it turned out, their house didn’t burn. The cameras went dark because the internet crashed. Through the weird swirls and gusts produced by the fierce Santa Ana winds, the fire jumped from their neighbor’s steep hillside slope to their backyard like an erratic king in checkers, burning other houses on the ridge above them, but miraculously leaving the Hinches’ home and a small patch of lawn intact.

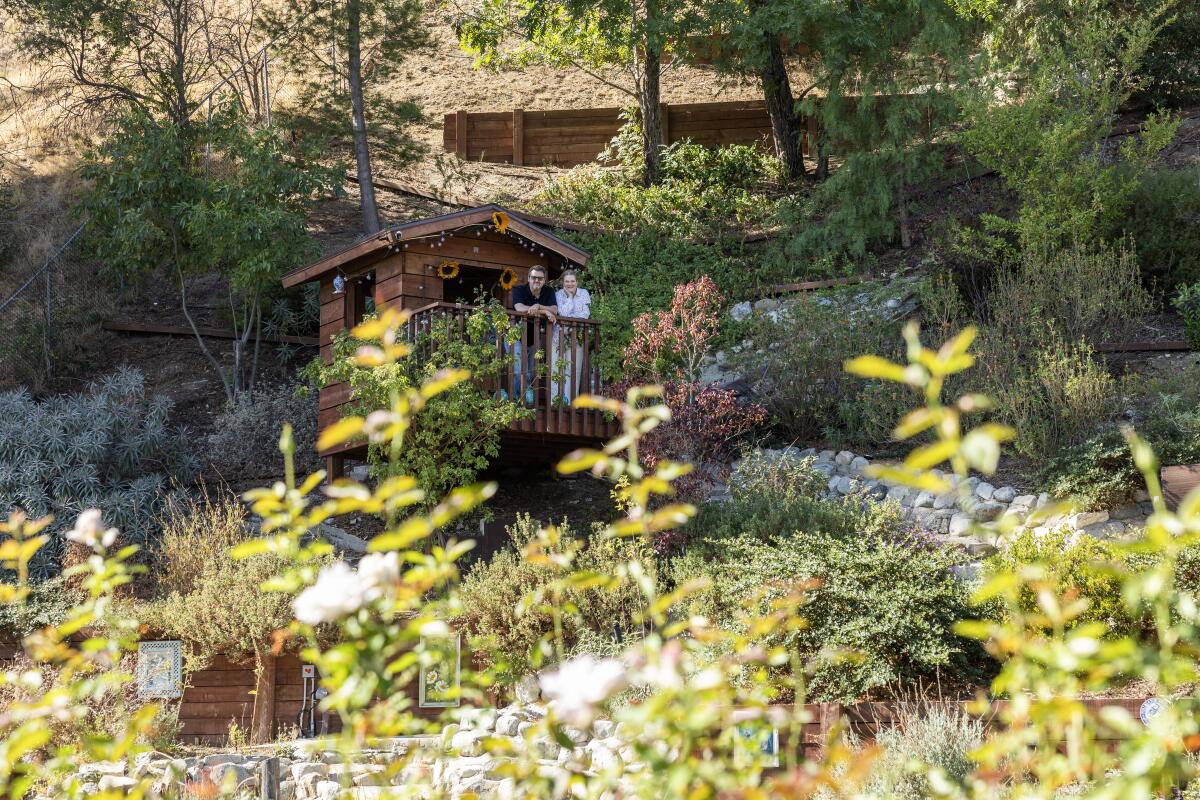

Phil and Margaret Hinch turned their Porter Ranch backyard into a mostly native plant landscape after the Saddleridge fire devastated it on Oct. 10, 2019.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The rest of the yard, however, was toast, “really, really burnt toast,” Phil recalled in an email. “When we could finally return to our home [two days later], the smell of smoke and ash was sickening. You never think about the smell when you see photos of fires like these. Walking the charred backyard was like being in a gigantic dirty BBQ pit.”

All the plants they’d recently added were burnt to a crisp, and the native endangered Southern California black walnut trees lining the top of their hill were charred and seemingly lifeless. The rock waterfall and koi pond built by a previous owner was choked with ash and once-smoldering logs firefighters threw in the water to stop them from reigniting. Much of the railroad-tie terracing had been damaged as well.

A small patch of grass and a few rose bushes next to the house were all that remained of the Hinches’ backyard. With Southern California’s rainy season fast approaching, their most immediate concern was shoring up their soil-scorched slope to keep the denuded hillside from sliding into their yard.

A path of river rock winds up the steep slope in Phil and Margaret Hinch’s backyard in Porter Ranch, leading past their rebuilt wooden playhouse and deck, which was destroyed by wildfire.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

There was a silver lining, however: They now had a blank slate to create a new landscape heavy on the California native shrubs and other water-saving Mediterranean-climate plants Margaret had long wanted to install.

They were excited about their huge yard when they bought the house in 2013. The family had been living in a cramped condo with their infant son, Jacob, and daughter, Olivia Fernandez, a 7 year old with dreams of her own outdoor playhouse.

Phil, an advertising executive, craved more space, and Margaret, a self-employed human resources consultant, wanted to raise bees and own enough land to follow her mother’s example as an avid gardener.

A miniature waterfall flows into a small rock-lined pond filled with native cattails. The home’s original owners designed the pond for koi, but the Hinches just keep mosquito fish now, because larger fish were constantly prey to raccoons and herons.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

More than half of their one-acre property was the steep hillside in their backyard, but unlike many of the slopes in their neighborhood, much of the hill had been terraced. Two of the home’s earliest owners, Russell and Elise Bauman, had “ruined two Cadillacs, a van and a pickup” hauling loads of “bowling-ball-sized river rocks” to build a waterfall, koi pond and pathway with multiple switchbacks that climbed almost to the top of the slope, said their youngest son, Kevin L. Eng, a health-care attorney now living in Santa Clarita.

Eng said he and his stepbrother Scott Bauman were tasked with helping his stepfather unload rocks from the car to the backyard and up the steep slope from the time Kevin was 7 in 1976 until he was 18. “They got a lot of joy out of that backyard,” recalled Eng. “It was their little labor of love — mostly my labor and their love.”

One of the reasons his parents sold the property around 2000 was because of the water costs, Eng said. And by the time the Hinches moved in, the landscape had been largely neglected, Margaret said.

It was just a huge lawn and a few rose bushes and shrubs.

This stone-lined concrete path was created by the house’s earliest owners, Russell and Elise Bauman, and their sons Kevin Eng and Scott Bauman, who hauled river rocks from the trunk of their car to the hill. Later, the Hinches added a bench as a resting place to admire the view.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Margaret and Phil’s happiness about their yard dimmed after they got their first water bill — roughly $3,000 for two months — and discovered they had used nearly 108,000 gallons of water during that time, mostly to irrigate their lawn.

“We were like, ‘What?!’ ” Margaret said. “We realized we needed to adjust to more drought-tolerant options as quickly as possible, so we tore out almost all the lawn, leaving just enough for someone to kick a ball on.”

She experimented with drought-tolerant trees and shrubs including lavenders and even bulbs like daffodils, but “I began to realize that so much of what I planted wasn’t doing well,” she said.

Then one day, hiking in the wild lands around their home, Margaret realized that the hills were covered with fragrant, beautifully blooming plants like lupine and sages. “I’d see these hillsides of absolute beauty in the spring,” she said, “and finally I thought, ‘Why am I not using what I’m seeing in my yard?’ ”

White sage is among the many native plants in Phil and Margaret Hinch’s Porter Ranch backyard.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The dried whorls of Cleveland sage flowers rise from the plant like wands.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

She began adding Cleveland sage, white sage, evening primrose, yellow lupine and other native plants in earnest, removing dead or poor-performing non-natives. Her native tree simply grew on their own, such as the black walnut trees and a small oak tree on the hill. Also, a graceful arroyo willow that sprouted near Margaret’s one-time vegetable garden now towers over the family’s home, attracting so many bees with its spring blooms that the branches seem to hum.

Almost all of the young plants and bark mulch the Hinches had added just a few days before the fire had to be replaced, but there were a few happy surprises.

The cleanup crew wanted to remove the blackened trunks and branches of the walnut trees, but Margaret told them no. It was fall, a time when the trees usually lost their leaves anyway, she said. “I just had a hunch they weren’t dead, and sure enough, in the spring, they started sprouting all these little green leaves!”

Switching to an all-native landscape is still a work in progress. After the fire, their landscaper, Anne Phillips of Go Green Gardeners in Van Nuys, recommended they plant fast-growing non-native plants such as flowering vinca vines and Pride of Madeira shrubs to stabilize the slope and prevent erosion from the impending winter rains. Those plants helped keep the soil in place and provided many lovely blooms, but Margaret’s goal is to remove them over time and replace them with native vines and shrubs.

A toy pterodactyl is one of many Easter eggs Phil and Margaret Hinch have placed in their yard to be discovered by children exploring the property, along with other treasures such as thrift-store paintings and silly signs and ceramics like the gnome-eating cat statue below.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Planting is hard work on a slope that’s nearly vertical in some places, so Margaret is adding plants gradually as well as wildflower seeds she hopes will take off in the spring. Although it initially felt counterintuitive, she’s found that small plants — such as those from 4-inch nursery containers — establish themselves and grow more quickly than larger, gallon-sized plants.

The re-landscaping hasn’t been cheap. Clearing the burned plants, amending the fire-scarred soil so it wouldn’t repel water, and buying new plants, landscaping cloth, berms to hold the soil and irrigation lines cost more than $26,000. But the Hinches now have drip irrigation on the hillside, plus large impact sprinklers that stand ready to wet down the property in the event of another fire. Rebuilding the large wood playhouse with its own little deck cost another $10,000.

To be more fire resistant, the Hinches also removed trees and wood bark mulch near the house and installed decomposed granite instead. And in 2022, during the height of the drought, they ripped out their remaining patch of lawn and installed artificial turf when they realized their irrigation water was going to be turned off.

The artificial turf gets way too hot, Phil said, but it provides a place for their son to play ball. When he outgrows that, he said, they’ll remove the fake grass and put in something else — Margaret is thinking about an herb garden.

One of the bonuses of their native plant garden is the many pollinators, birds and other wildlife attracted to their Porter Ranch yard, said Margaret Hinch. “The squirrels can get quite aggressive if I get too near ‘their’ walnuts,” she said with a laugh.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

And their water usage now? It’s dropped enormously, from 108,000 gallons for two months in 2013 to less than 20,000 gallons total this past July and August, reducing their costs to about a quarter of what they paid in 2013. Many of the native plants are in their summer dormancy now, but the garden is still a quilt of greens in every shade, along with native roses and non-natives like lavender and lion’s tail for splashes of color.

Margaret embraces her garden’s dormancy. “We need to be mindful of the environment we live in,” she said, and that this is a time when native plants rest, retreating from the heat. There’s still beauty and interest in the garden with dried stalks and seed pods providing food for the birds and other animals.

Also, the muted colors of late summer make the vibrant riot of spring blooms all the more beautiful, she said. They have so many flowers, they make bouquets and wreaths to share with friends and neighbors. And they host outdoor movie nights and neighborhood gatherings in their yard. And sometimes, she said, neighbors just come to sit quietly and take it all in.

For Margaret, it’s all part of achieving the garden of her dreams. “It’s like my mother always said: ‘A garden must be shared.’ ”